Walking along a stream, roadside, or the edge of a field on a breezy day, you may catch flashes of silver in the greenery. Take a closer look. You might have found a pocket of autumn olive – a beautiful, but invasive shrub with an interesting story.

Identifying autumn olive

Autumn olive (Elaeagnus umbellate) is a fast-growing leafy shrub that reaches up to 20 feet in height and forms dense thickets along the sunny edges of streams, rivers, roadsides, and forests. Their leaves are oval-shaped and somewhat wavy along the edges. While the top of the leaf is green with silver specks, the back is solidly silver – to the point that it looks like it's coated with metallic silver spray paint. This standout characteristic arises from the tiny silvery-white fibers that coat the underside of the leaf.

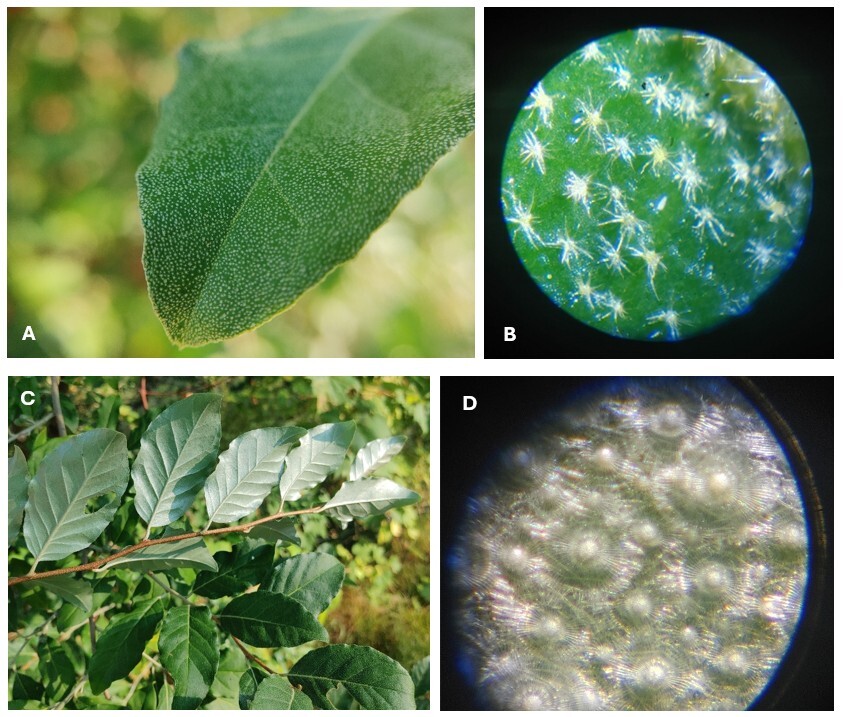

Autumn olive leaves have small silvery-white fibers that interact with light to produce a silver appearance. The top of the leaf (A) has silver speckles while the bottom of the leaf (C) is completely silver. When seen through a microscope at 60x magnification, it is easy to see the fiber clusters are spaced apart on the top of the leaf (B) while they form an intricate, tightly woven tapestry on the underside of the leaf (D).

In spring, autumn olive is one of the first plants to leaf out. Within a few weeks, it grows clusters of small, light-yellow flowers. As spring turns to summer, the flowers mature into small greenish-silver olive-shaped fruits. By the time September arrives, there is no mistaking the autumn olive shrub, as all the fruits mature into lush clusters of silver-flecked red berries.

The silver-flecked red berries of autumn olive shrubs make them easy to spot in late summer and early fall.

Autumn olive's interesting history

With so many beautiful features, it's no surprise some pioneering individuals back in the 1830s thought autumn olive would be a wonderful addition to gardens here in the United States. Brought here from East Asia, the shrub was considered a prized ornamental plant. Later, in the 1960s, the shrub was promoted by the US Department of Agriculture for use as windbreaks, wildlife habitat, erosion control, and mine reclamation. Unfortunately, the shrub thrives so well in poor soil conditions, it quickly took over swaths of landscape, outcompeting native plants and dramatically changing ecosystems. Today, it is listed as a severe threat in some parts of the US. Here, in the Adirondacks, it is considered a species of concern by the Adirondack Park Invasive Plants Program (APIPP).

Support our biodiverse habitats work for wildlife and their habitats. Give with confidence today!

Species of concern

There is a lot more going on with autumn olive than meets the eye. Underground, this invasive shrub is able to access critically needed nitrogen in nutrient-poor soils. It pulls off this impressive feat with the help of symbiotic bacteria (Frankia) that live in the shrub's root nodules. The bacteria pull nitrogen (N2) straight from the air and use it to produce ammonia (NH3), giving the plant a ready resource of this essential nutrient.

The round clusters shown here are root nodules of an autumn olive shrub. Symbiotic Frankia bacteria live in the root nodules, making nitrogen readily available to the plant. Inset: a view of root nodules through a microscope at 60x magnification.

Thanks to their bacterial partners, autumn olive thrives in just about any soil conditions and can easily outcompete native plants. As with other invasive plants, the problem here is the formation of monocultures – large areas that contain only one species of plant. The lack of biodiversity is problematic for insects, birds, and other animals (including fish) because it changes the availability of food and habitat. Additionally, monocultures make ecosystems more vulnerable to pests and diseases. For example, if a disease infected and killed autumn olive, the area occupied by the monoculture would be more prone to erosion and other negative ecological impacts.

How does autumn olive spread?

Autumn olive spreads in two major ways: by seed spread and by resprouting from cut roots or stems. Mature shrubs can hold 8 pounds of fruit, all of which is popular with birds and other animals such as racoons, skunks, and opossum. Seeds grow readily when dispersed by these animals as well as when fruit drops off the shrub. New plants also grow if the shrub is clipped or its roots are broken. Because of this, mowing is not an effective means of removing autumn olive.

Managing autumn olive

If you identify autumn olive on your property, the first step is to determine the extent of the problem. If your shrubs are small, you can loosen the soil around them and pull them out of the ground. The entire root system must be removed to prevent resprouting. The best time to accomplish this is before any berries turn red. Marking the location with a colored stake or flag makes it easy to monitor the location for new growth.

If you have mature shrubs or if your shrubs cover a large area, chemical control methods are usually recommended. Several agencies provide detailed guidance for this approach to autumn olive management, including APIPP and the Missouri Department of Conservation.

Bonus info

If your shrubs have already produced their beautiful berries, you can harvest them before removing the plant. This prevents the seeds from spreading and also provides you with a culinary treat. Autumn olive berries are edible for humans and are rich in vitamins and lycopene. While they can be eaten raw, they are quite tart and fibrous. To overcome this, the berries can be cooked, strained, and pureed. In this form, they can be used for jams, jellies, sauces, fruit leather, and smoothies. They are also used to prepare mead and wine.

Story and photos by Marque Moffett, Stewardship Manager.

Sign-up for our e-newsletter to get weekly updates on the latest stories from the Ausable Freshwater Center.