Catch-and-release fishing is a great way to enjoy the outdoors in a conservation-friendly way. There are many simple steps anglers can do to increase the survival rates of the fish they release back to the river. In part one of our two-part blog, we covered temperature limits for catch-and-release trout angling. Here in part two, we explain the best options for fish hooks, nets, and fishing line, as well as best practices for catch-and-release such as keeping fish wet and minimizing fight time.

Gear Choices

Fish Hooks:

Proper gear starts with choosing the right hook. By looking at size, material, and presence or absence of a barb, we learn that certain hooks cause less injury than others and improve the survivability of a fish who swallows the hook.

Barbed hooks are a common piece of gear due to the idea that the angler will be less likely to lose the fish; however, the injury rates associated with barbs and the dehooking tools often used with them are very high. Barbless hooks are associated with lower mortality and injury rates and are also much easier to remove. No one’s idea of a peaceful fishing trip is fighting to pull a barbed hook out of a fish’s jaw only to end up hooking your own hand. Since many flies you might purchase already have barbs on them, you can crimp the barbs off yourself with a pair of flat-nosed pliers. Your local fly shop will have a selection of barbless flies and flat-nosed pliers.

Hooking location is often the determining factor in whether an angled fish survives. A hook injury to the esophagus, stomach, or gill arches is commonly fatal, or, at the very least, reduces growth. Preventing the fish from swallowing the hook is often as easy as using the right size hook. Still, sometimes bad hook injuries occur, but they will be less significant if one uses barbless hooks or cuts the line if the fish is deeply hooked, rather than pulling at it or using the “through the gill” method, which causes further injury.

Hook size refers to the range of hook sizes you might use to catch a particular “class” of fish. Anglers often use light line and smaller hooks to reduce visibility in the water, but a hook too small for the targeted species is more likely to be swallowed instead of catching the fish in the lip. Don’t go smaller than the recommended hook size for the size and species that you’re going for.

Type of metal has a slight effect on mortality if the fish swallows the hook and the line is cut. Stainless steel is the least damaging metal type. Most flies are tied on steel hooks.

Hook type, size, and material as well as hooking lcoation can all influence the survival of a fish following a catch-and-release encounter.

Net types:

Net injuries are not easily noticed because the effects of the injury often show hours after release. Certain net types cause fin fraying or mucus and scale loss, which renders the fish susceptible to infection, particularly the fungus Saprolegnia.

Fin damage from net use can lead to difficulty swimming to catch food or to evade predators. This can lead to stunted growth over time or eventually, death. Injured fins are also susceptible to fin rot.

The mucus and scales on a fish are like the fish’s skin. The fish’s mucus layer has antimicrobial (antifungal and antibacterial) compounds and even defends the fish against UV rays. It is important not to completely remove the mucus layer when handling the fish or by using abrasive net material.

Knotless rubber nets are the smoothest material with which to handle fish and cause the least amount of damage to fins and scales, when compared to bare wet hands, rubber-coated nylon, nylon, and knotted polypropylene. Using large sized mesh (less net surface area) will also reduce scale and mucus loss compared to fine mesh.

While all nets cause some amount of scale or mucus loss, this can be mitigated by choosing the correct net type and being gentle with the fish even when it is in the net. Always wet the net before use.

Choose your net carefully to avoid excessive scale or mucus loss. This is an example of a knotless rubber net which can help reduce injury to a fish.

Support our biodiverse habitats work for wildlife and their habitats. Give with confidence today!

Best Practices

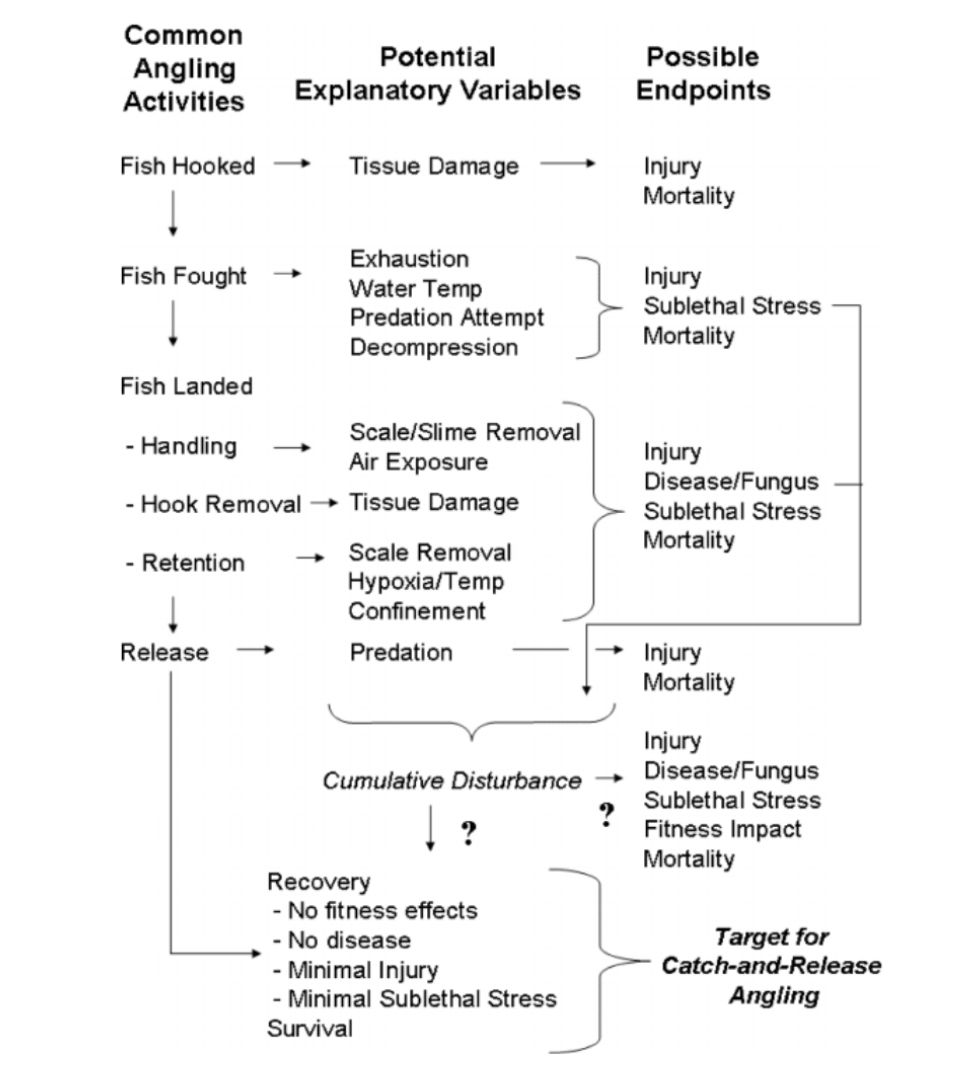

Once you’ve chosen the right gear, it’s all about following ethical angling practices. Extended time playing the fish, air exposure, and handling time have all been found to increase mortality rates by predation and other factors, and to have a significant effect on the fish’s overall stress level, or the energetic cost associated with combating the cumulative amount of stress the fish is exposed to. Stress can result in return to normalcy/homeostasis, or it can have long term effects on life functions, such as growth, feeding ability, predator avoidance, and reproduction. It is up to the angler to reduce stress on the fish and increase its likelihood of returning to normalcy.

Reducing fight time:

While it’s always more fun to bring in a brown trout fighting the line than a walleye hanging on like a wet sock, anglers should never intentionally drag out the time that fish is on the line. Increased fight time alters the fish’s pH, cortisol, lactate, electrolytes, hydromineral balance, and blood glucose. Much like the human body, a fish that’s exerted itself will need real food (not the fly you just fed it) and time to return to homeostasis.

To reduce fight time, use one pound heavier line than what you think you need and avoid letting the fish fight or play out more line than is necessary. Additionally, keeping the fish submerged after you catch it allows it to breathe and recover faster. If the fish doesn’t swim away upon release, revive it by facing it upstream in the water or by gently rocking it back and forth to allow the running water and dissolved oxygen to pass through the fish’s gills.

Keep fish wet:

Another way to reduce unnecessary stress on fish is to keep fish wet at all times. Wet your hands and the net before handling your catch to prevent damage to the fish’s slime coat. After you’ve landed your fish, keep it submerged to avoid unnecessary stress until the camera is ready.

Wet your hands, lift the fish, photograph, and immediately release, limiting time out of water.

Exposure to air:

Holding fish out of water for an extended time while viewing, photographing or removing the hook greatly decreases their survival rate. This is because their gill lamellae collapse out of water and are unable to effectively transfer gases in this way. When returned to the water, their heart rate is increased and their body pH is thrown off. Extended air exposure temporarily affects swimming ability during recovery which can lead to difficulty feeding or to the fish being displaced downstream in potentially subpar habitat. Keep air exposure to a minimum, aiming for ten seconds or less.

This juvenile wild brook trout was submerged until the camera was ready and then lifted barely out of the water for a quick photo before gently releasing it.

In summary, ethical fishing aims to improve fish recovery time, survival rates, and the overall stress the fish is exposed to. Even small seemingly insignificant efforts towards reducing stress on angled fish have been shown to reduce mortality rates after the fish is released.

Simplified schematic of the main factors that influence catch-and-release fish recovery and survival. Figure from Arlinghouse et al. 2007.

The main takeaway for ethical catch-and-release angling is the same message for the whole of conservation: it is up to the individual to follow best practices, especially in angling which often goes unobserved by others. No one is standing over your shoulder counting the fight time seconds, telling you the water temperature, examining scale loss in each angled fish, or reminding you to wash your gear to prevent the introduction of invasive species. It is up to each of us as individuals to take responsibility for conservation.

Story by Naomi Hodgson, River Steward.

Sign-up for our e-newsletter to get weekly updates on the latest stories from the Ausable Freshwater Center.