Healthy riparian vegetation is the glue that holds streambanks together. Plants play a critical role in the hydrology, hydraulics, and geomorphology of a functioning stream corridor. When we restore a section of river in our watershed, much of the focus turns towards the engineering and construction of the channel, with natural boulders positioned to reduce stress on banks, maintain pool habitat, and prevent the streambed from downcutting. However, that is only the beginning of a recovery process that can take years. With our short growing season and the dynamic conditions that exist along flashy river channels such as the East Branch Ausable, we have continued to adapt our restoration maintenance to meet the challenges posed by an unforgiving environment.

While the most obvious role of vegetation in a riparian setting is to bind and anchor soil that reduces erosion caused by flowing water, plants also add roughness and alter the hydraulics of the channel and floodplain. Rougher surfaces dissipate energy and reduce the velocity of water along the banks, which encourages the deposition of finer particles: silt and sand. This retains nutrients and kicks off a healthy cycle of richer growth, trapping and building better soils that feed a thriving riparian ecosystem. Over time, these ecosystems grow upward and outward to help guide the development of natural channel features such as riffles, pools, and point bars. Vegetation reinforces the self-adjusting nature of rivers and allows the channel to maintain a stable form that is resilient to flooding and moves water and sediment effectively.

Excess sediment is the main water quality issue we face in this region. Restoring our riparian forests is critical to reducing sediment loads that are primarily the result of eroding banks throughout the watershed. While the Ausable River is known for having a large sediment supply (sable is French for sand), too much sediment causes problems. It can smother fish spawning gravels and destroy macroinvertebrate habitat, disrupting food webs.

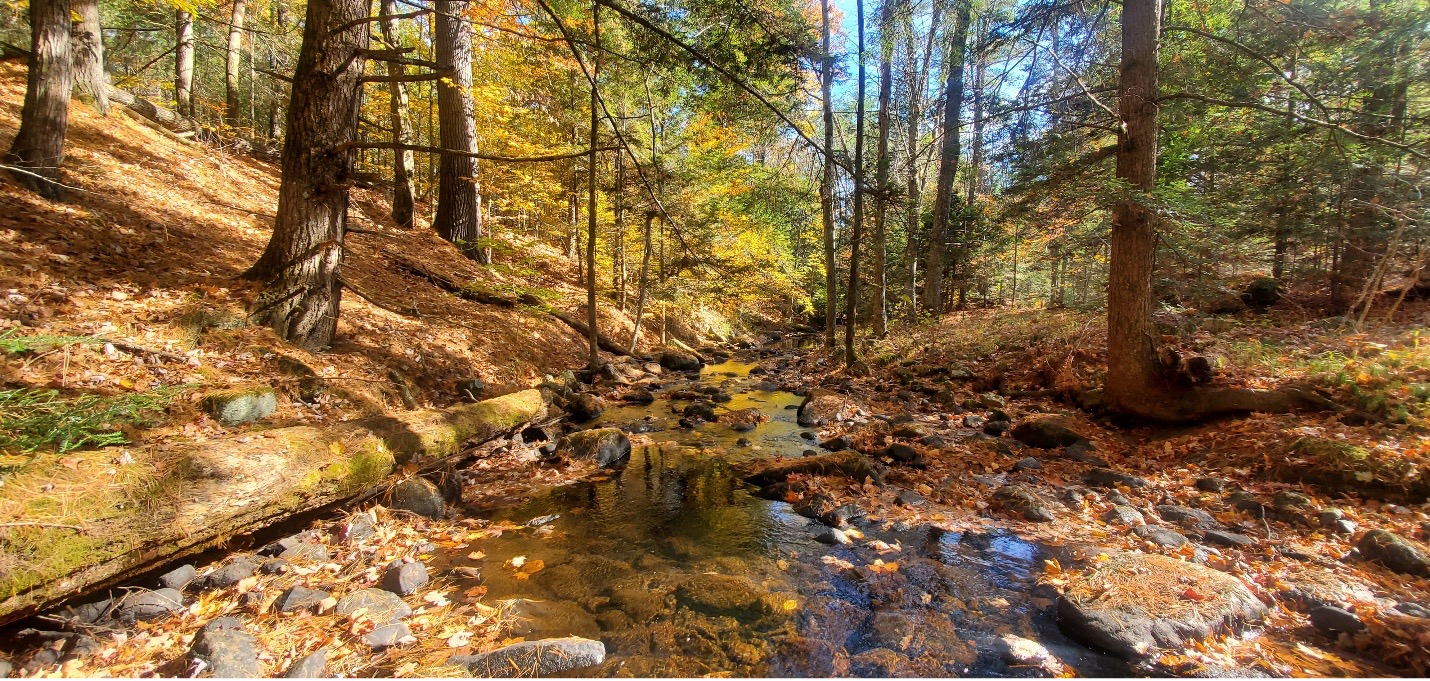

The shade given by riparian trees helps to regulate stream temperature, another key water quality issue in our region. Elevated water temperatures can be lethal to brook trout and other sensitive species. Leaf litter and canopy cover also create cool, humid microclimates that benefit riparian wildlife.

Streams and forests evolved together, and the woody debris from riparian areas is an important component of a functional aquatic ecosystem. In a natural, forested stream, downed trees provide logs and rootwads that scour pools, sort sediments, and provide habitat for fish and invertebrates. While our designs typically incorporate wood to create more geomorphic complexity, re-establishing the riparian forest will help to provide long-term sources of woody debris and organic matter.

Healthy vegetation protects streambanks from erosion. It also feeds the aquatic ecosystem with leaf litter that drives detrital food webs and woody debris that adds habitat complexity.

Riparian zones are biodiversity hotspots, supporting birds, mammals, amphibians, and insects. Vegetated streambanks offer nesting and foraging areas, while root complexes and overhanging vegetation provide refuge for fish and invertebrates. Leaf litter and organic debris from riparian vegetation serve as a primary energy source for stream ecosystems, fueling the detrital food web. Restoration of riparian forests has cascading benefits for ecosystem productivity and resilience.

Vegetation supports the self-healing capacity of river systems. Once established, plants interact with geomorphic processes in ways that enable streams to adjust naturally, reducing the need for ongoing intervention. While engineered boulder enhancements help kickstart the healing process by redirecting flows and creating new habitat, the long-term success of a river restoration project depends upon the establishment of a healthy buffer of dense riparian vegetation. The buffer grows and adapts, becoming stronger and more effective with age. Riparian forests continue to provide ecological functions for decades or centuries, outlasting the design life of engineered treatments. By harnessing natural processes, riparian restoration improves resilience to disturbances such as floods, droughts, and climate change.

This restored streambank was enhanced with logs and rootwads from downed trees to mimic the natural recruitment of woody debris and its associated complexity. Over time, the re-establishment of a riparian buffer will supply this vital resource to the river channel as the engineered channel enhancements reach the end of their design life.

The benefits of riparian recovery are well understood and yet may be difficult to achieve. Vegetation is most vulnerable during the first few years after restoration. Extreme flooding is always a risk and can damage plants before they are well established. Young vegetation is often grazed by wildlife or can be stunted by dry conditions in any given year. Hardy, invasive species can rapidly colonize disturbed areas and outcompete native vegetation during the recovery process.

Over time, we have adapted our approach to riparian restoration as we learn more about our local ecosystems and the interactions between river and forest. We want to mimic the mature forests that with luck exists on the opposite bank, but we also need to start by planting early successional species that will help build the habitat for late successional species (canopy trees) to grow. To figure out the best species list to apply to fresh banks as building blocks for a mature ecosystem, we studied other habitats along the river corridor that were highly disturbed (by ice or flooding) and bare ground. We compiled detailed lists of all species growing across several sites and used these to create species mixes for grasses, flowering plants, ferns, and early successional shrubs.

The restoration work we have laid out is ambitious, and includes several acres of new banks and floodplain access nearby. The idea of creating the Ausable Conservation Nursery took root in early 2020, and began as a small fenced-in plot in Lake Placid. As we’ll need several thousand, or tens of thousands, of trees and shrubs at our project sites alone, it became clear that we should pursue the creation of an entire nursery to grow hyperlocally adapted plants. This project is the fruition of the seeds we planted long ago.

Story by Gary Henry and Carrie Pershyn

Sign-up for our e-newsletter to get weekly updates on the latest stories from the Ausable Freshwater Center.